Pisa Tipped, Physics Flipped

Introduction

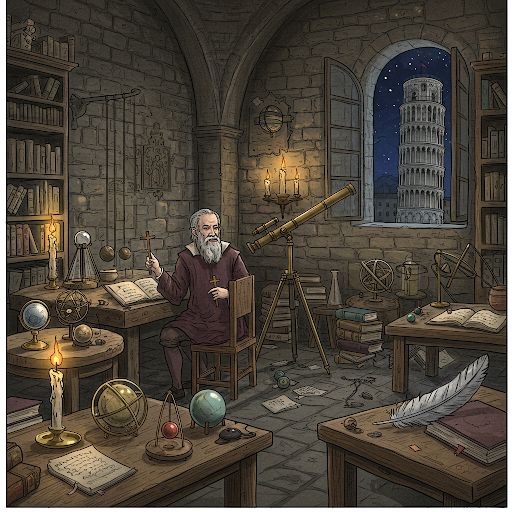

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, and mathematician whose discoveries and methodologies laid the groundwork for modern science. As a key figure in the Scientific Revolution, he is often called the “father of observational astronomy,” the “father of modern physics,” and even the “father of science.” His groundbreaking use of the telescope, contributions to motion and mechanics, and advocacy for heliocentrism profoundly shaped our understanding of the natural world.

Born in Pisa, Italy, Galileo showed an early aptitude for mathematics and science. Although initially enrolling in medical studies at the University of Pisa, he soon shifted his focus to mathematics and natural philosophy, influenced by the work of Archimedes and Euclid. His early work on pendulums and hydrostatics foreshadowed his later contributions to physics.

Galileo, with his improved telescope and unwavering commitment to empirical evidence, challenges the long-held beliefs about the cosmos. “Observe,” he declares, his voice filled with a quiet passion, “the celestial bodies themselves, and let your eyes be the judge of truth.” He points to the moons of Jupiter, circling their parent planet, and to the phases of Venus, mirroring those of our own Moon. “These observations,” he insists, “reveal a universe far different from the one described by ancient authorities.”

Contributions to Astronomy

Galileo’s most famous contributions stem from his improvements to the telescope and his subsequent astronomical observations. With his enhanced telescope, he made several key discoveries:

The phases of Venus, providing evidence against the Ptolemaic geocentric model.

The four largest moons of Jupiter (now called the Galilean moons), proving celestial bodies orbit objects other than Earth.

The rugged surface of the Moon, challenging the Aristotelian notion of perfect celestial spheres.

Sunspots, contradicting the belief in an unchanging, flawless heavens.

His astronomical work provided crucial support for the Copernican heliocentric model, which placed the Sun at the center of the solar system rather than Earth.

The Battle for Heliocentrism

Galileo’s support for heliocentrism was controversial, as it opposed the geocentric model endorsed by the Catholic Church. His 1615 writings led to an investigation by the Roman Inquisition, which concluded that heliocentrism could only be regarded as a hypothesis, not an established fact.

Despite this, he later published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which presented a compelling argument for heliocentrism. The book, perceived as an attack on Pope Urban VIII, led to Galileo’s trial and house arrest. While under arrest, he wrote Two New Sciences, summarizing his decades-long work on motion and materials science.

Contributions to Physics

Galileo’s experiments in motion were revolutionary. His studies on falling objects led to the realization that objects accelerate uniformly under gravity, independent of their mass. This insight refuted Aristotle’s claim that heavier objects fall faster.

Key contributions to physics include:

The principle of inertia: Objects in motion stay in motion unless acted upon, foreshadowing Newton’s First Law.

The law of free fall: The distance fallen by an object is proportional to the square of the time elapsed (d ∝ t²).

The pendulum’s periodic motion, influencing later developments in timekeeping.

These ideas introduced the mathematical treatment of motion, making Galileo a precursor to classical mechanics.

Galileo and Modern Science

Galileo’s legacy extends beyond his lifetime. His principle of relativity—the idea that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames—laid the foundation for later developments in physics, including Einstein’s theory of relativity.

In the context of modern physics:

Time-Symmetric Interactions: Galileo’s insights into motion and symmetry align with modern quantum wave equations, which are often time-reversible.

Quantum Nonlocality: His rejection of Aristotelian assumptions echoes contemporary debates about the fundamental nature of space-time and entanglement.

Legacy

Despite his struggles, Galileo’s work permanently altered humanity’s understanding of the universe. The Church eventually lifted its ban on heliocentrism, and in 1992, Pope John Paul II formally acknowledged the errors made in Galileo’s trial.

Today, his name is synonymous with scientific rigor, observation-based reasoning, and the courage to challenge dogma. His famous quote encapsulates his spirit: “I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended for us to forgo their use.”

His contributions, spanning astronomy, physics, and philosophy, continue to inspire scientific thought and inquiry. Galileo remains a pivotal figure in the advancement of human knowledge.

The Way Forward

“Look,” Galileo beckons. You press your eye to the lens. Jupiter’s moons—four of them—drift against the void. Not fixed. Not tethered to Earth. The heavens, once immutable, now move with undeniable precision.

You notice a collection of detailed astronomical drawings, meticulously recording Galileo’s observations of the heavens. Mathematical calculations support his claims, demonstrating the elegance and precision of the heliocentric model. A copy of his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems lies open, its pages filled with arguments that challenged the very foundations of the prevailing worldview. A fragment of a letter lies nearby, bearing the inscription: “Observe the heavens, trust your senses, and dare to challenge the dogma of ages.”

In addition to looking at the heavens, He secretly conducted experiments on the speed of falling objects, laying the groundwork for understanding gravity and acceleration, though not definitively measuring the speed of gravity in the modern sense. Galileo rolls marbles down a slanted board. “See? All smack dirt same beat.

He grins. “Mystery is the clue—being heavy does not affect the glue.” Fall speed don’t care for mass—Aristotle’s bunk.”

Objects fall at the same rate regardless of mass.

To the Past: History beckons—Pythagoras begins the quest of melding mathematics with mans understanding.

To the far north: A windmill sways—Christiaan Huygens pendulums whisper their secret.

To the west: A tribunal awaits—judgment lingers in the Vatican halls…