Nature’s Logic, Unraveling.

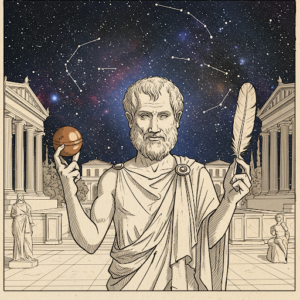

322 BCE, Athens. A polished marble arch rises—Λύκειον etched deep. The Lyceum courtyard, a place of intellectual discourse and observation, where layers of logical thought and natural philosophy intertwine. The polished marble arch, “Λύκειον” etched deep, stands as a gateway to knowledge. Inside, olive trees dapple the light, casting shadows on scrolls that spill from shelves, their layered writings hinting at Aristotle’s vast observations.

A Student of Plato, He had fundamental disagreements. Aristotle is often seen as a key figure in the development of empiricism, which holds that knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience and observation, while Plato’s philosophy emphasizes the role of reason and abstract thought.

A faint, layered diagram of Aristotle’s categories overlays the scene, its logical structure echoing through the courtyard. Aristotle, his eyes filled with contemplative wisdom, gestures towards a collection of natural specimens. “Observe,” he intones, his voice resonating with the echoes of his teachings, “the layers of nature, the palimpsest of categories.”

He points to a dissected animal, its anatomy overlaid with faint sketches of its underlying principles. “From the smallest insect to the grandest cosmos,” he declares, “all things are organized by inherent logic, a system layered within the very fabric of existence.” A scroll lies nearby, filled with his writings on logic and natural philosophy, with faint, erased lines beneath the current text, like older ideas being built upon. It bears the inscription: “Unearth the layers of logic, decipher the categories etched in time, and understand the natural world through reason.”

Scrolls list the Four Causes: material, formal, efficient, final. A mosaic half-glows—Plato’s Cave, shadowed by this sunlit truth. Theophrastus scratches a horse onto wax—biology’s seed. A sundial hums faintly, time’s pulse.

Natural Place:

Aristotle’s theory centered on the idea that all objects have a natural place in the universe, and they move towards it.

Geocentric Universe:

He envisioned a geocentric universe, with the Earth at the center, and the elements (earth, water, air, and fire) having their own natural places around it.

Natural Motion:

He believed that the natural motion of objects is circular, and that the natural motion of the elements is towards their respective natural places.

Earth and Water to the Center:

Earth and water, being the heaviest elements, naturally move towards the center of the universe (the Earth).

Air and Fire Away from the Center:

Air and fire, being lighter, move away from the center, with air surrounding water and fire above air.

Speed Proportional to Weight:

Aristotle believed that objects fall at a speed proportional to their weight, meaning heavier objects fall faster.

Three arches loom:

North: A Challenge—Galileo: “But why, are you still playing with your balls or have you lost your marbles?”

East: Forum echoes—Socrates’ ghost taunts, “Seek my ignorance paradox.”

South: Dim hall, torchlit—Euclid’s lines whisper, “Order hides in geometry.”